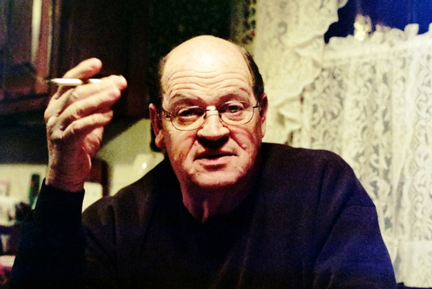

Man in the Chair

It is late in the afternoon on a fall or winter day, and I am visiting my mother and stepfather at their home in Rome, New York. They are sitting in their family room watching TV; if I had to guess, I’d say the show is Judge Judy, Criminal Minds or NCIS. My stepfather Bill, who owns his own contracting business, is reclining in his favorite chair, wearing a work-stained hoodie and sipping a cup of coffee. I walk into the room and sidle up to him. I put my hand on the bald crown of his head, which has a fringe of brownish-gray hair on the sides, and I feel the warmth emanating from his skull. Often when I do this, Bill will say, “God your hand is freezing.” But he does not say anything, and I leave my hand on top of his head and take a glance at the television screen while darkness gathers outside the windows.

A sick realization makes me shudder. I pull my hand away because I recognize in the moment that the head of this man I love could, in a matter of seconds, be crushed with a baseball bat or cracked open with an axe blade. Blood could splatter against the walls and he would slump over in the chair, inert.

And I think this not because I am homicidal or possess a desire to kill my stepfather. Quite the opposite. Fear sets in because I realize the man sitting in the chair, with a beating heart, functioning brain and sense of humor, could be gone in an instant.

He could be animated in one moment and his breath snuffed out in the next.

Most likely my stepfather will not be killed by a blow to the head or a tree crashing through the house. A heart attack, stroke or cancer will probably get him in the end. And while I already know this, I pause and allow this knowledge to sink in, so I will appreciate him better.

A year or two later my mother would lose her battle with cancer. And her death would remind me that we do not live life all at once. It’s not one big project we have to complete by a set deadline or a trip to Europe you have planned for years.

Instead we experience life in small doses, tiny beads of time on a string. And it helps to recognize them, to acknowledge you are present and alive even in the most mundane circumstances—while you are talking with co-workers in the parking lot before heading home for the day, running errands, doing laundry, baking a chocolate cake, tossing a football with friends, reading to your kids at bedtime. These are subplots that drive our stories forward. They are not exciting. They are not memorable. But they are part of our existence and we have to value them before they and we are gone.

So, after I pull my hand away from Bill’s head, I decide to sit on the couch next to my mother. She hates when people talk during a program because it distracts her, so I look at the screen even though I am not interested in the show, and I do not say a word. But during a commercial break, she mutes the sound with the remote control, and Bill and I converse about something. And I can’t remember the topic we discussed, and it doesn’t really matter.

Francis DiClemente lives in Syracuse, New York, where he works as a video producer. In his spare time he writes and takes photographs. He is the author of three poetry collections, In Pursuit of Infinity (Finishing Line Press, 2013), Vestiges (Alabaster Leaves Publishing, 2012) and Outskirts of Intimacy (Flutter Press, 2010).